Author’s note: I started drafting this post in early August. I researched, wrote, cut, added right back. Then life got busy with school starting back and my own lack of interest, and this post almost went in the deleted bin.

Then Jacob Blake got shot, and I realized I had been lulled into passivity. So here I go.

If you’ve never met Ken Heffner, you’re missing out.

In my sophomore year at Calvin, I worked with Ken in a position called a Cultural Discerner. Cultural Discerners worked in the dorms to foster conversations about how we as Christians engaged with pop culture. It was through my time as a Cultural Discerner that I was introduced to the concept today’s post is about, finding the sacred in the profane.

We’ll get back to that. Instead, let’s talk about the present. Specifically, three incidents that have started the biggest movement of the century.

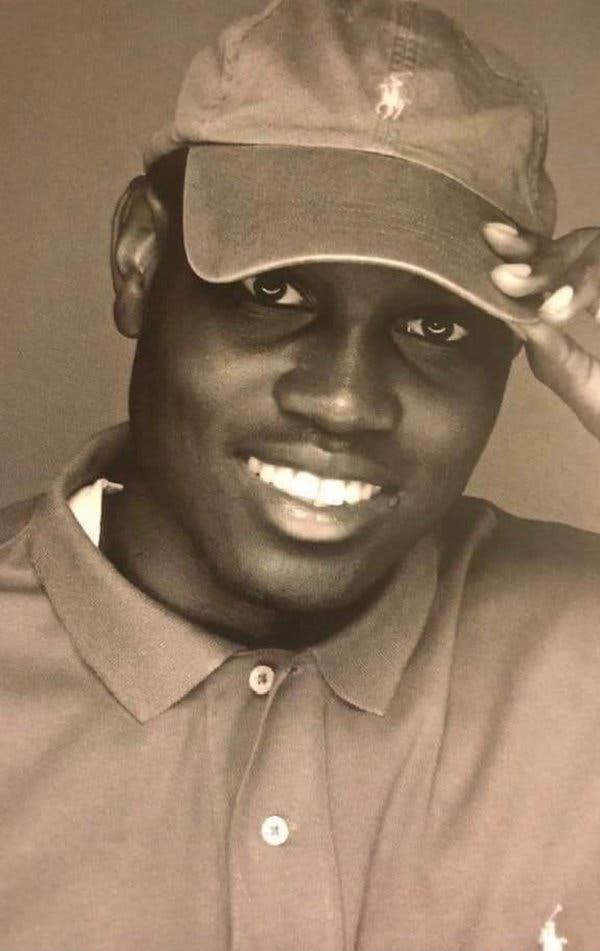

On February 25 in Brunswick, Georgia, 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery was accosted by a white father and son and one of their neighbors while he was out on a run. Arbery was pursued by the three men in two vehicles, cut off by the neighbor, and fatally shot by the son. Despite the neighbor catching the whole thing on video and none of them being law enforcement (therefore having no authority to use lethal force), it took almost three months for the three men to be arrested and charged.

At midnight on March 13, 2020, three members of the Louisville, Kentucky, police department executed a no-knock search warrant on the apartment of 26-year-old medical technician Breonna Taylor and her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker. The warrant was for two men allegedly involved in drug dealing, neither of whom lived in Taylor and Walker’s apartment. The police broke into the apartment using a battering ram, waking the couple from sleep. Walker, a licensed gun carrier, retrieved his gun and fired a shot at the intruders and received almost two dozen rounds of return fire, which killed Taylor. Walker was initially charged with assault and attempted murder of an officer, but the charges were dropped. As of the publishing of this post (September 14), one officer has been fired, but none have been arrested or charged.

On May 25, George Floyd allegedly paid for a pack of cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill. The police were called on Floyd when he refused to return his purchase. After he was cuffed, Floyd was first sat in the back of a police cruiser, then pulled from the car by Officer Derek Chauvin. Four officers restrained Floyd while he was on the ground, one by sitting on Floyd’s chest, and Officer Chauvin by putting a knee on Floyd’s neck. Floyd was in this restraint for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, during which he said multiple times he couldn’t breathe (both because of his air being cut off and his recent recovery from COVID-19), cried for his mother, and finally lost consciousness and stopped breathing. Floyd was pronounced dead an hour later. All four of the officers who restrained Floyd were arrested, Chauvin’s trial for second-degree murder is currently pending, and the other three officers have been charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder.

Everyone (and I do mean everyone–including the founders of Ben & Jerry’s, one of the head honchos of Reddit, Mitt Romney, witches and Batman) had something to say. The protests against police brutality and for systemic reform went international, making the Black Lives Matter cause one of the biggest in history.

Christian communities had a…shall we say, mixed reaction to the protests. On the one hand, Christian sects that had been neutral on the matter of racial equality were finally pushed off the fence; see: the notoriously-conservative Southern Baptist Conference’s change of heart and the United Church of Christ’s affirmation of the Black Lives Matter cause. On the other hand, the protests made bigoted Christians dig their heels in further. But keep in mind, there’s a good reason for the indecision on the topic of Black Lives Matter.

Christianity, especially in America, has a long history of being on the wrong side of racial issues. If we’re strictly talking American Christianity, we could talk about the use of Scripture to justify slavery; the many white supremacist organizations, past and present, who twist theology into evidence for racial purity and calls for violence; that the primary force that stood against Martin Luther King, Jr. and the civil rights movement were white Christians; or the continued support by white evangelicals for President Trump through his many racially-charged and discriminatory statements and policies. If we wanted to go international, we could talk about the long history of antisemitism in European Christianity, coming to a climax with the Third Reich cherry-picking Martin Luther’s writings to make a Christian justification for Nazism.

The end result? What to the rest of the world seems like a black and white issue is subsequently muddled by the church’s history of being complicit or actively engaged in racism.

Flipping the perspective, Christians have their own issues with BLM, as has been expressed both in discussions and to me personally. It’s an issue with a few key parts of Black Lives Matter’s mission statements:

We are guided by the fact that all Black lives matter, regardless of actual or perceived sexual identity, gender identity, gender expression, economic status, ability, disability, religious beliefs or disbeliefs, immigration status, or location.

We make space for transgender brothers and sisters to participate and lead.

We are self-reflexive and do the work required to dismantle cisgender privilege and uplift Black trans folk, especially Black trans women who continue to be disproportionately impacted by trans-antagonistic violence.

We disrupt the Western-prescribed nuclear family structure requirement by supporting each other as extended families and “villages” that collectively care for one another, especially our children, to the degree that mothers, parents, and children are comfortable.

We foster a queer‐affirming network. When we gather, we do so with the intention of freeing ourselves from the tight grip of heteronormative thinking, or rather, the belief that all in the world are heterosexual (unless s/he or they disclose otherwise).

–From the “What We Believe” page on the official Black Lives Matter website, all emphases mine

Now, it is here I have to narrow down my audience. I’m not talking to people who focus on the violence that’s broken out at BLM protests. I’m not talking to conservative Christians who prioritize the “conservative” over the “Christian”. I’m not talking to reactionary Christians. I’m not talking to Christians who reject anything liberal or left-leaning on impulse or are anti-“woke” or who reject BLM for its part in “cultural Marxism,” whatever that even means. I’m talking to Christians on the fence, Christians who believe marginalized people are being crushed under the boot of white supremacy but are still reluctant to embrace the Black Lives Matter cause.

During my time working with Ken Heffner, we read The Soul of Hip-Hop by black theologian Daniel White Hodge.

Throughout the book, Hodge examines rap music, in particular artists like Tupac, KRS-One and NWA, as well as protest music. From his analysis, Hodge pulls a theology of justice from the lyrics: lyrics that look to heaven and cries out to God that He would deliver the justice institutions refuse to. Along with his theological weaving, Hodge criticizes the church’s knee-jerk rebuffs of hip-hop and attempts to co-opt the sound of black music to provide a “Christian” (read: white) alternative for young people.

Above all, Hodge begs his readers to find the sacred in the profane. To refrain from the church’s recoiling at the drug references and tales of sex and violence and look deeper, to the stories of losing friends to gang violence, of being racially profiled by police, of fatherlessness due to mass incarceration, and of groaning under the weight of systemic racism. The music cries out to God for justice because earthly forces of justice have often been the primary tool of their oppression.

If you are reluctant to take up the Black Lives Matter cause, I encourage you to find the sacred in the profane. Look to the roots of Black Lives Matter, a movement created in response to the death of Trayvon Martin.

On February 26, 2012, one man, a man with no legal authority to use lethal force, took the law into his hands and sentenced Trayvon Martin to death for the heinous crimes of wearing a hoodie and buying a bag of candy. It was a story black people everywhere had heard a million times before, but this time it was different: the killer wasn’t a police officer. There was no brass shield for George Zimmerman to hide behind, so maybe, finally, someone would answer for spilling an innocent young black man’s blood. The judge’s reading of “not guilty” gave a message loud and clear: Black Lives Don’t Matter. It wasn’t the brass shield on the breast of your shirt that gave you the permission to be judge, jury and executioner for people of color, but the color of your skin.

We as Christians need to recognize that the Black Lives Matter movement exists largely because of a stinging failure on the church’s part. The days of Martin Luther King organizing marches from a sanctuary are gone. For decades after King’s death, black Christians have been crying and begging at the church’s door for help, any kind of help, only to be turned away with responses of “All lives matter!” “Oh, we don’t talk about that here.” “Racism is a heart issue. That’s between them and God.” After decades of the church whistling and twiddling its thumbs, the church has unintentionally broadcast a tragic message: if people of color want justice, don’t go to church.

But we can do better. We can tell our black brothers and sisters that Jesus weeps for the deaths of his sons and daughters and so do we. We can march. We can advocate. We can educate ourselves. We can start hard conversations, bringing God into what was previously a secular discussion. We can make real change in God’s name.

I encourage you, reader: look for the Christian motivations in Black Lives Matter’s secular language.

Find the sacred in the profane.

Thank you all for reading. I hope you were moved by today’s post. I want to keep making contributions to the conversations we as a nation are currently having. With that in mind, I formally introduce Today I Want to Talk About… (TIWTTA)

This is a new series on the blog, where I break down hot-button topics, sociological concepts, and anything else relevant that comes to mind. With this series, I want to do my research and give a good resource that cuts through all the hysteria and presents information without an agenda. At the end of each post, I’ll present resources for further reading.

The first TIWTTA‘s subject: privilege. Stay tuned!