Music is always changing.

The so-called “top genre” has shifted multiple times in my lifetime. In the 1990s and into the early 2000s, rock dominated the music scene, first with grunge bands like Nirvana and Alice in Chains, then in post-grunge bands like Limp Bizkit, Nickelback and Breaking Benjamin. In the mid-2000s and going into the 2010s, pop music and R&B would overtake rock. Hip-hop would reach a peak of popularity in the late 2010s, before pop music would reclaim the top spot in the 2020s.

But among the genre wars, among new factors like the rise of Spotify and TikTok and their subsequent influences on popular music, something else happened.

Music got sadder.

Before we continue, let me give you my definition of “sad music.” “Sad music,” in my humble opinion, is music that fits any of the following criteria: 1. Music composed in minor key. 2. Music that deals with dark or bittersweet topics (death, mental illness, infidelity, etc.) 3. Music that utilizes musical techniques associated with sad music (ex. slow tempo, quiet or low vocals, lyrics centered around loss, longing for better times, etc.)

Now, sad music has always existed. And even in the time periods people look to when they say music used to be happier, sad songs were still popular. Peter Rugman, the TikToker duetted in the above TikTok video, singles out the time period of 2007 to 2016 as a happier, more upbeat time in pop music. Scanning through the Billboard Year-End Hot 100 of those years, here’s a list of sad songs that charted in those years:

- “Hey There Delilah” by the Plain White T’s

- “It’s Not Over” by Daughtry

- “What I’ve Done” by Linkin Park

- “Face Down” by the Red Jumpsuit Apparatus

- “Apologize” by OneRepublic

- “You Found Me” by The Fray

- “Second Chance” by Shinedown

- “Love the Way You Lie” by Eminem and Rihanna

- “Not Afraid” by Eminem

- “If I Die Young” by The Band Perry

- “Rolling in the Deep” by Adele

- “Someone Like You” by Adele

- “Just a Kiss” by Lady A

- “Somebody That I Used to Know” by Gotye and Kimbra

- “Set Fire to the Rain” by Adele

- “A Thousand Years” by Christina Perri

- “Mirrors” by Justin Timberlake

- “Wrecking Ball” by Miley Cyrus

- “Let Her Go” by Passenger

- “Stay with Me” by Sam Smith

- “Say Something” by A Great Big World and Christina Aguilera

- “Stay the Night” by Zedd and Hayley Williams

- “See You Again” by Wiz Khalifa and Charlie Puth

- “Take Me to Church” by Hozier

- “I’m Not the Only One” by Sam Smith

- “Hello” by Adele

- “Wildest Dreams” by Taylor Swift

- “Girl Crush” by Little Big Town

- “One Last Time” by Ariana Grande

- “7 Years” by Lukas Graham

- “Lost Boy” by Ruth B

In addition to that, multiple artists that made a downbeat sound part of their brand rose to fame and/or saw continued success between 2007-2016: megastars like Adele, Sam Smith and Hozier; bands like Shinedown, Linkin Park and Lukas Graham; and one-hit wonders like Gotye, Passenger and the Red Jumpsuit Apparatus.

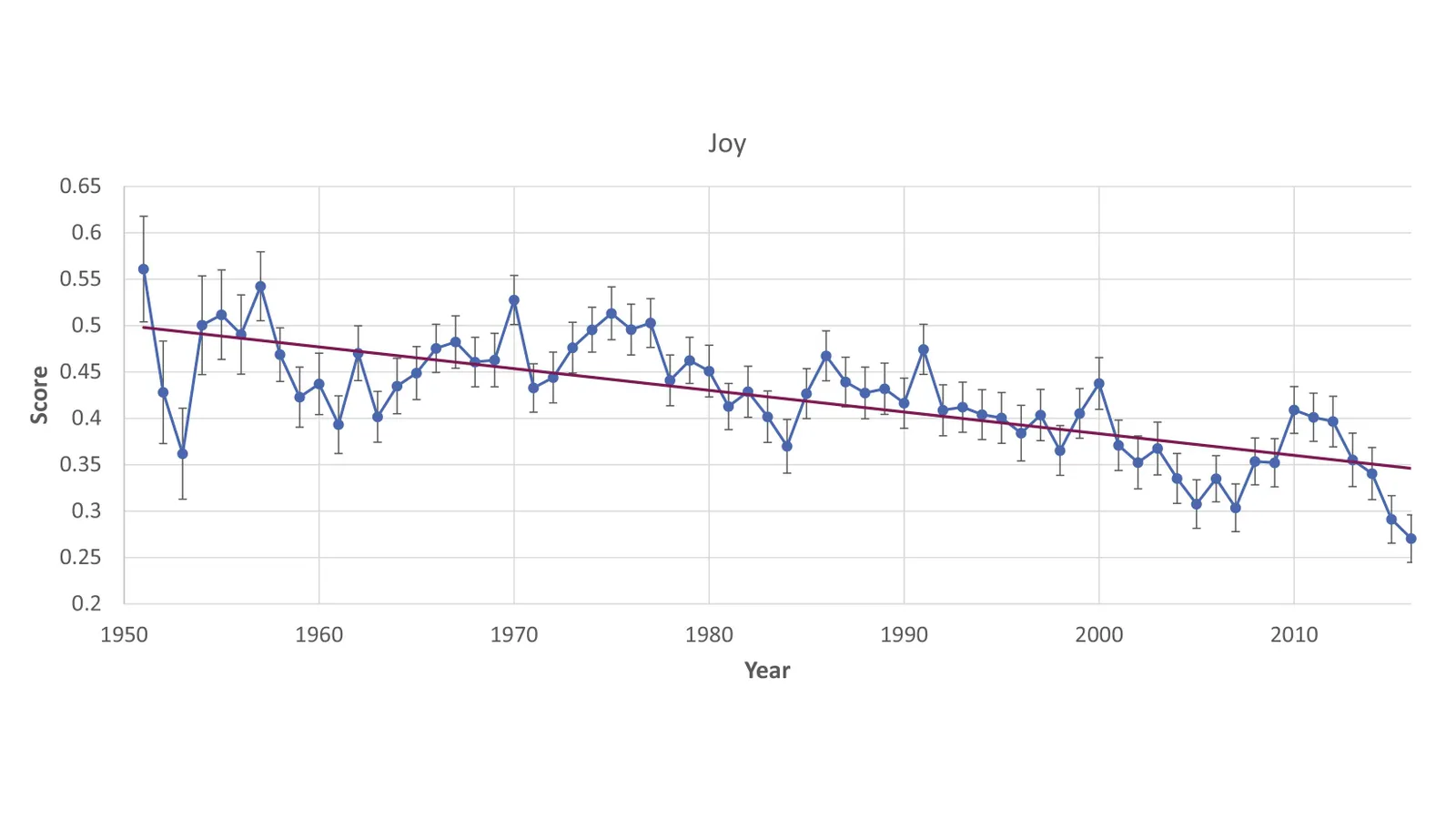

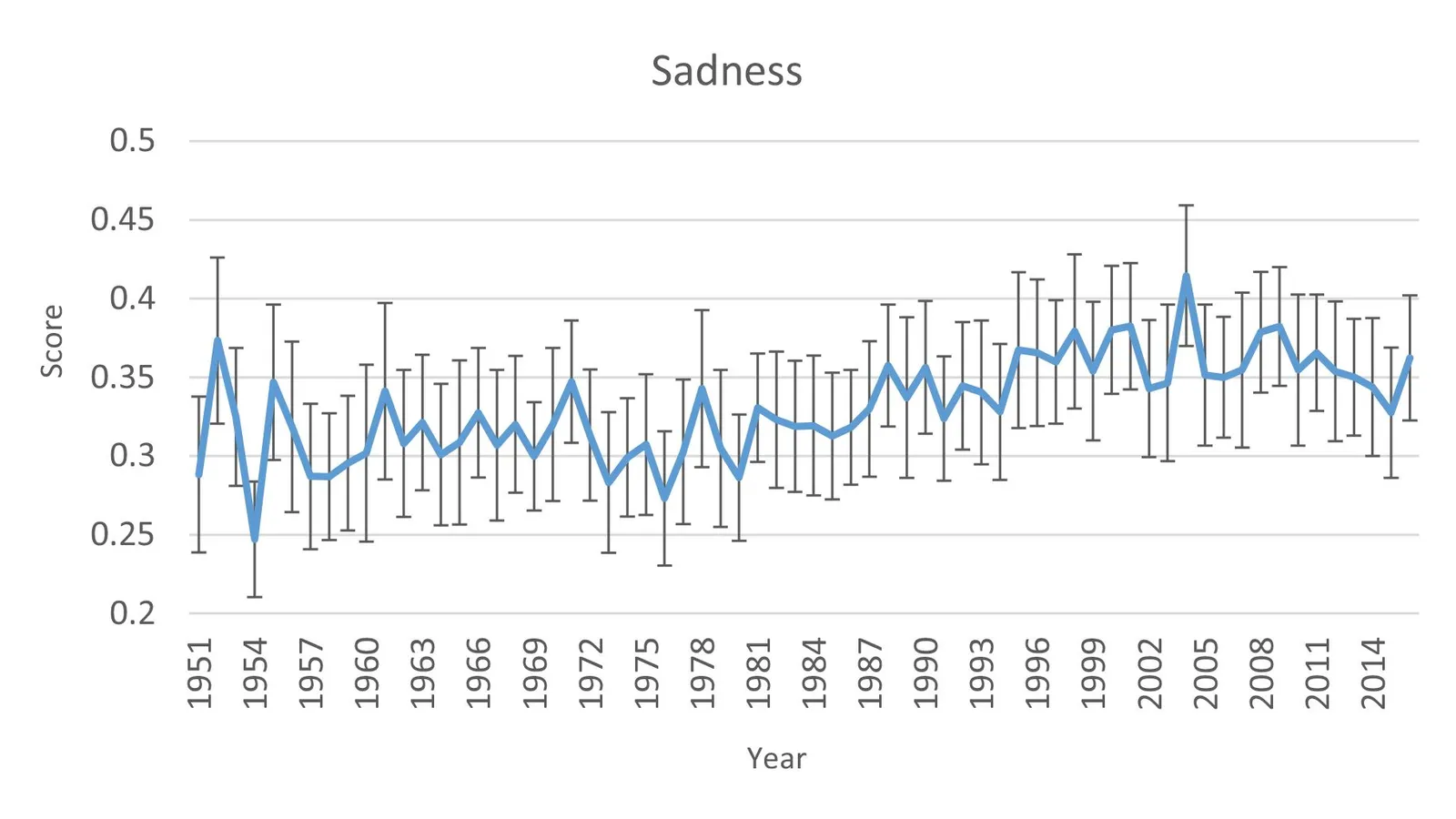

All of what I’ve so far presented is anecdotal evidence, but there is hard evidence for music becoming sadder…but that hard evidence flies in the face of the assertion that the music world having a depressive episode is a recent phenomenon. Lior Shamir, a computer science professor who formerly taught at Lawrence State University and currently teaches at Kansas State University, performed an experiment in 2019. Using an algorithm, he analyzed the lyrical content of songs that reached the Billboard Hot 100 between 1951 and 2016. The algorithm measured different emotions–joy, happiness, fear, sadness, anger and disgust–in song lyrics on a scale from 0 to 1. Shamir found that in the 7-decade span the algorithm analyzed, lyrics displaying positive emotions like joy and extraversion steadily declined, while lyrics centered around negative emotions like sadness, disgust and fear steadily increased…starting in the 1950s. BBC and Inside Science both reported on Shamir’s experiment. The following images are charts the BBC article included in their article showing the decrease of joyful lyrics and increase in sad lyrics:

What does this mean? Contradicting Señor Rugman’s assertion, even in the period of 2007-2016, as well as other supposedly upbeat periods in music history like the early 1960s and most of the 1980s, music was getting steadily sadder, angrier and more cynical.

But whether the music industry’s feeling blue started 7 years ago or 7 decades ago, a question hangs over this whole observation: why is music getting sadder?

We can get our first answer by looking at when music started to get sadder. Shamir’s study looked at music from the 1950s up to the mid-2010s. To oversimplify 50 years of music, music in the 20th century’s first half was a vehicle of escapism. From the jazz of the Roaring ’20s to the bubblegum pop of the ’50s to the first few lighthearted outings of the Beatles in the early ’60s, music in the first five decades or so of the 1900s was made with the intention of nodding your head along and snapping your fingers, something to put on to forget the stresses of work and school. But in the early ’60s, everything went to hell. John F. Kennedy’s violent assassination in front of hundreds acted like a hammer, shattering the peace and idealism of post-WWII America. The civil rights movement, the Stonewall riots, and the early waves of feminism opened a lot of people’s eyes to the inequality and bigotry ubiquitous in American society. The assassination of civil rights leaders–Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., Medgar Evers, Robert Kennedy, Fred Hampton–squashed people’s hope for a more equal and progressive society. The Vietnam War, the Kent State massacre, Watergate, and suspicions that several civil rights leaders’ deaths were government-ordered (suspicions proved right in at least one case, albeit decades later) destroyed the good faith the likes of Franklin Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower, and John F. Kennedy in death had built for the US government. And those are only American examples. Abroad, the many dictatorships of the 20th century and the economic and societal devastation of the World Wars were (understatement of the century) real mood-killers worldwide.

All of this cynicism needed an outlet, and for a lot of people, musicians and listeners alike, that outlet was music. The protest song, an old form of music, gained new life, as folks like Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs and Johnny Cash would produce some of the genre’s greatest hits. Outlaw country, a form of progressive country highly critical of American society, took off in the late ’60s and going into the ’70s. Acts like John Lennon and Bruce Springsteen and bands like Rage Against the Machine made addressing social issues part of their brand. A whole sub-genre of rap, conscious hip-hop, speaks on societal problems. See: Kendrick Lamar and J. Cole.

The second part of the answer? A lot of “happy” music isn’t as happy as people make it out to be. Going back to the Peter Rugman video, he pins down 2007-2016 as a happier time in music. These were also the years where the US (and the world in general, but especially the States) experienced the Great Recession. Much like the late 1960s, everything went to hell in 2007 and 2008. The graduating classes of those years graduated into the worst economy possible. Single people, parents, retirees, all across the board plunged into financial instability or outright poverty even when they did everything right. And yet, at this time of worldwide depression, music got a pep in its step. There’s a name for the era of music Peter Rugman zeroes in on: “recession pop.”

Let’s return to my definition of “sad music” briefly. When most people think of a sad song, they think of something gloomy, something slow, maybe with violins or piano, maybe tackling something serious along the way, depression or divorce or death or some other personal crisis starting with “D.” Those are two parts of my three-part definition of sad music, but let’s consider the third: music that deals with dark or bittersweet topics. So-called recession pop does, but indirectly. Most sad music tackles sad things head-on, but recession pop does so through escapism. Your girlfriend left you, you’ve got a master’s degree but you’re working at Starbucks, you’re pretty sure your parents are wondering why they had you, and you’ll never own a house. Here’s the Black-Eyed Peas!

Most people, either by name or by concept, know about “lyrical dissonance,” when gloomy, depressing or otherwise not-happy lyrics are paired with cheery upbeat music. See: Sia’s “Chandelier,” a song about an alcoholic going on a binge; Justin Bieber’s “Love Yourself,” a cute little ditty where he gives his terrible ex both barrels in song form; and Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal,” a song about Annie being attacked and likely murdered by her criminal ex-boyfriend. Recession pop traffics in mood dissonance, cheery-sounding music meant to distract listeners away from their real-life problems.

How do I conclude a post like this? I don’t know. Despite people’s personal feelings about this, there’s nothing inherently bad about a song being sad or a musician making a downbeat sound part of their brand. The only thing I can think to say is: I hope in the future, the world improves to the point we don’t need sad music, of the conventional type or the sneaky recession pop type, as an emotional crutch.